Squint, Reanimate: Un Oeuf Scrambled & Portmanteaus for Brunch

(Puzzles and Poems for the Placidly at Home)

04/26/20

by Jesse Malmed with Tim Donovan, Jessica Campbell and Chris Reeves

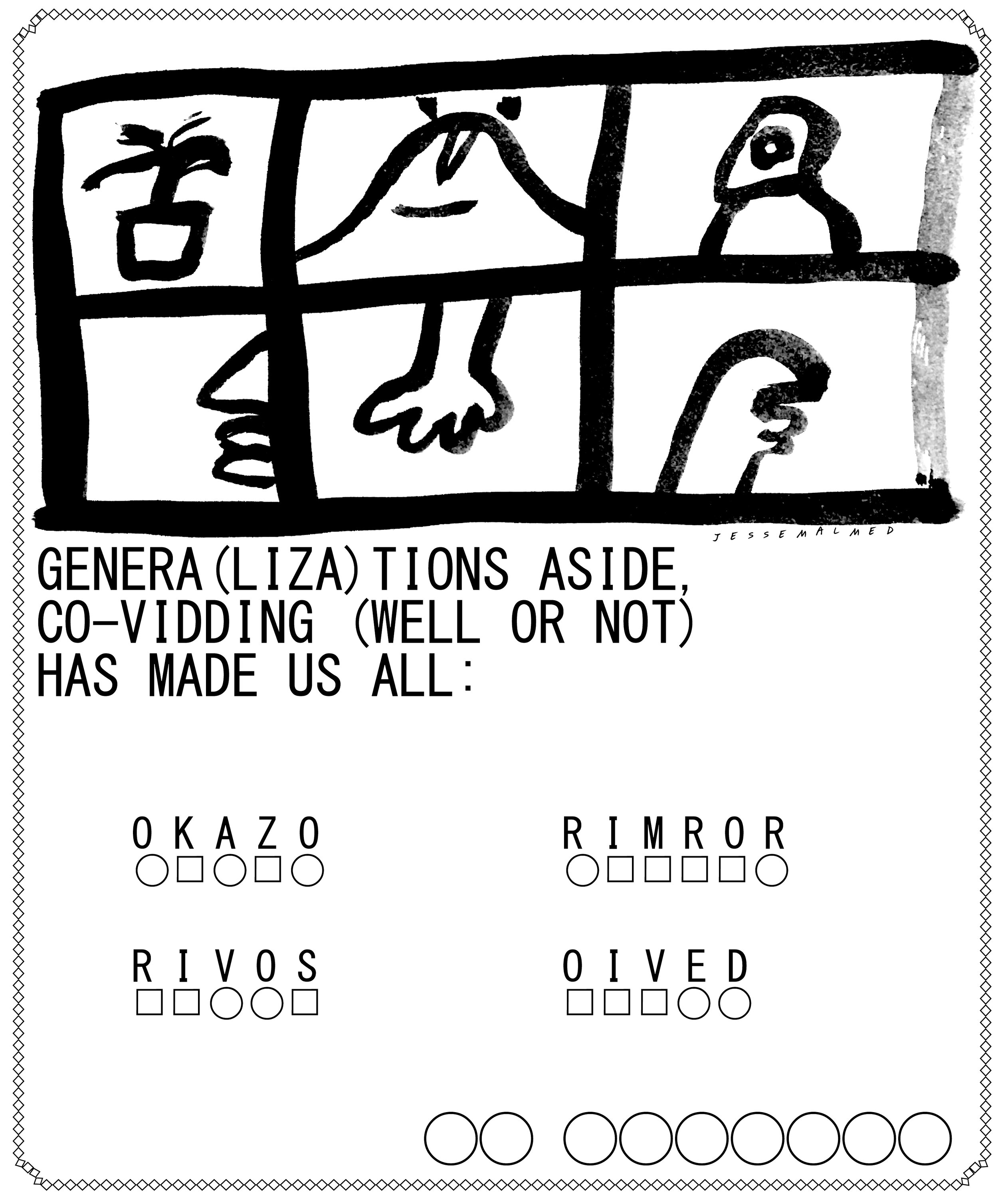

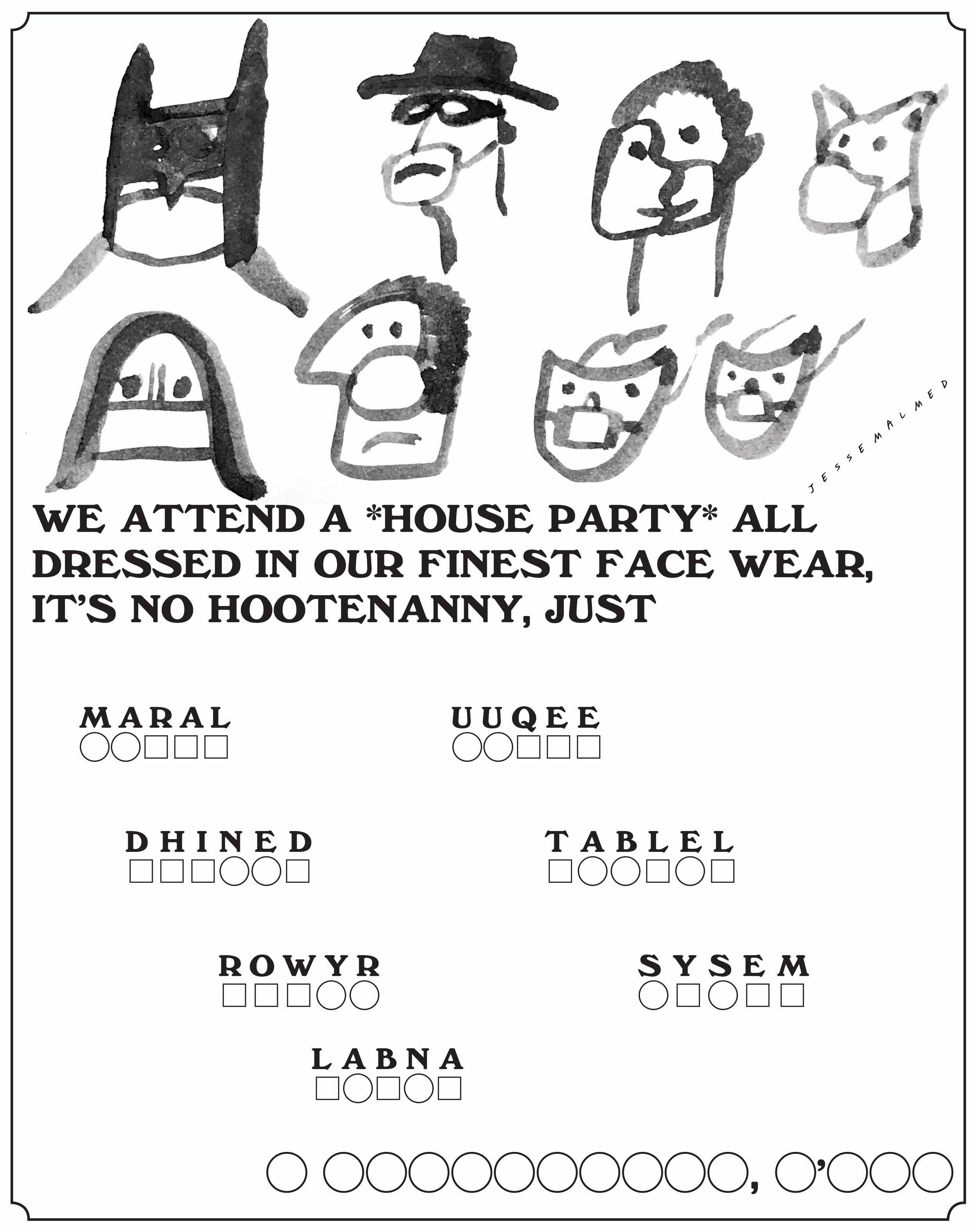

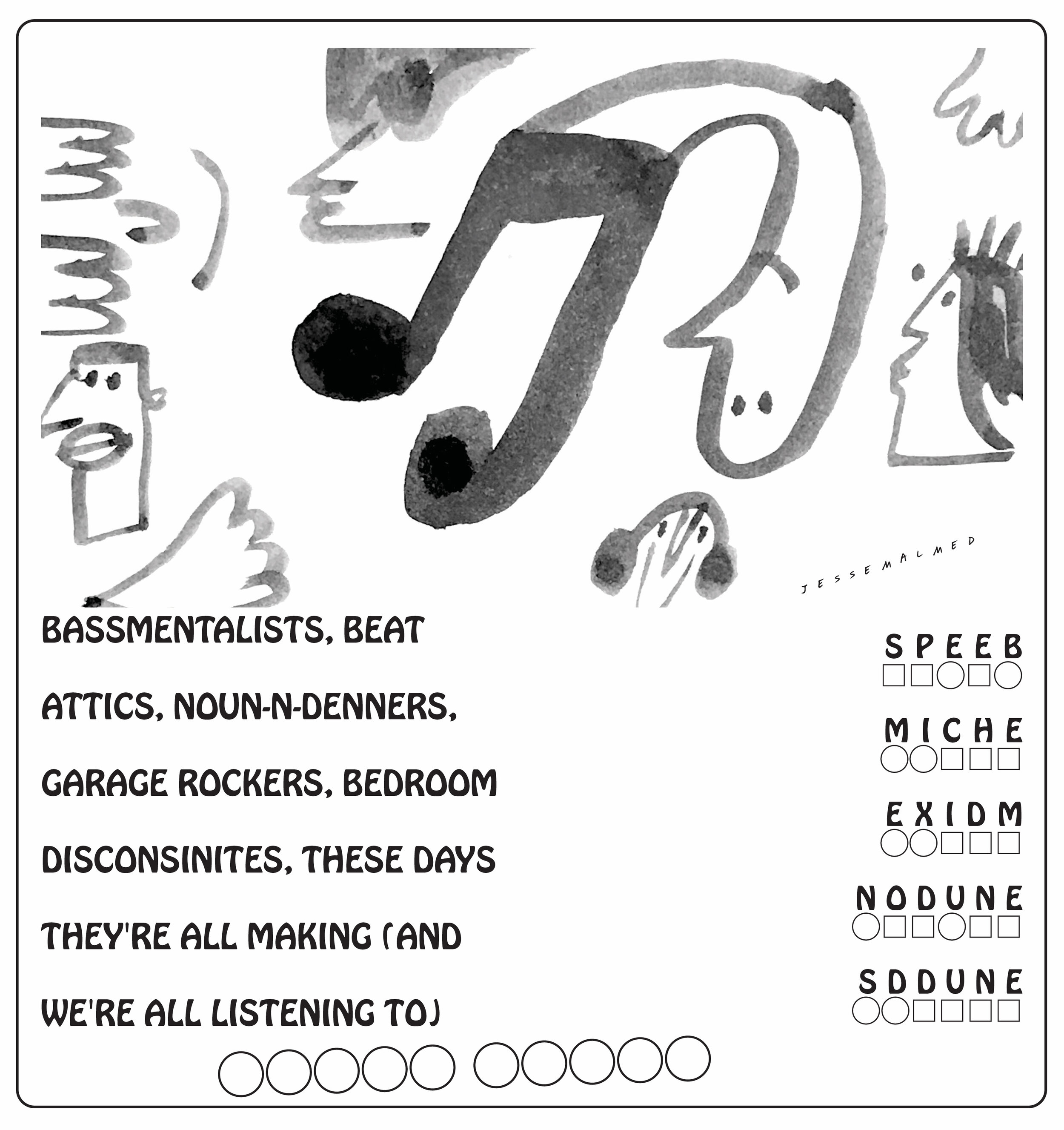

For years and, I think, years, I have been making jumbles. They’re that newspaper puzzle form where the audience is presented with a riddly bit, a series of nonsense words meant to be anagrammed back into sense that, once filled into their appropriate boxes of squares and circles, reveal letters (the encircled ones) that together form a scrambled series of letters which, in the right order, fill in the answer to the riddle at the beginning. I made them throughout college, where they were published in the scrappy but esteemed Bard Free Press. They were littered with inside jokes, nods to what I was reading, friends whose visages made for cute cartoons and, too often, typos. I recall once realizing an error and being able to leverage the school’s email list to atone and correct the record.

After college, I offered these to different art publications and printed them in occasional zines. Throughout, I’ve been interested in how these might fit into other practices—especially the idea of puzzles as poems. To me, this is an easy jump: one pleasure of reading and of experiencing art generally is to treat the text as something to be entered, to be deciphered, to bring what Charles Bernstein termed (and I borrowed, in the title of a film) wreading, that is to say a kind of reading as writing, a postmodern prioritizing of creative reading and the role the audience fills in creating meaning from art. All art is interactive, few works are vacuums and even fewer exist within them, requiring an audience to give them sense, to make them sing, to close the circuit.

By literalizing the collaborative relationship of author and reader, puzzles reveal something about the pleasures of the thinking that goes into encountering art. Cruciverbalists can tell that their work has been apprehended fully in a way that other difficult poets may not. At the same time, this mode presents an obvious problem: that there is a single *correct* way of interpreting a work. Very few crossword puzzles have the flexibility to contain multiple answers and those that do feel much more virtuosic than the obvious openness even your avant-garden variety abstraction has. It’s why we don’t use mirrors tilted at the clouds as traffic signs, at leastnot anymore. I have felt and thought (and am happy to talk about how and when we use those terms interchangeably, and how and when we think of them as opposites or at least distinct categories)—do feel, will think, feel like I might think, have thought that I was feeling—that if an artist intends a work to say just one thing and say it boldly then maybe they’d do better just to say that one thing. Iin teaching, I have often found that younger artists are consumed by the notion of a one-to-one symbolism that I suspect comes from clunky instruction around literature and art that, in asking for deep reading through the matrix of standardization, insists that this is that, that that red is passion, this dove is peace, the scarecrow is farmers, Shaggy is Hampshire College. Something like a semiotics of sameness and simplicity, text that can be added on top of a meme format, political cartoons with characters in declarative sashes. To indulge in a cliché sesh: not to say that a cigar is always a cigar, but it might not always be a phallus.

There’s a long, lovely, and lively history of artists using puzzles—or what I’ll call puzzle-thinking—in their doing and making. Nabokov wrote crossword puzzles; James Joyce said of Finnegan’s Wake that “I’ve put in so many enigmas and puzzles that it will keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant, and that's the only way of ensuring one's immortality”; the Oulpians made it an essential component of their practice and ethos; Fluxus artists centered play in their work (or vice-versa); my friend Ben Segal made this excellent work of crossword fiction a few years and lives ago; The Smudge and Colleen Hammond have just published a slim volume of crosswords; the lists go on, ever on.

I like a puzzle like I like a joke like I like a magic trick. Or as they sing, “if you like metaphors/ you’ll love what they’re for.” If SoCal media (what?—their weather report is nicer and accents more soothing than Illin’ dot whatever) is any indicator, lots of people are getting into jigsaws as a type of family and friendly quaranti time. It’s something about the level of paying attention, I hear, shaping that impulse. It’s interesting enough to keep minds moving and out of anxious alleys but not so enthralling that you’re kept up all night. I imagine a wand-ward sign, a wreparative wreading that follows the magician’s misdirection right into a whole new place.

So, ok, onto today. It’s Sunday and it’s time for a few treats. Here are a few stabs at immortality, diversion, repair, play, etcetera that should spark your mind and this moment. I’m grateful to today’s guests, Tim Donovan (whose email address itself is a puzzle), Chris Reeves and Jessica Campbell, to the PMI folks for including me in this process and to my crack team of proof-readers. To quote every email in the last 40-some days, I hope that you are well and staying safe in these terrifying times.

The play is the work is the play is the work is the play,

Jesse

(Download the Printable PDF)

(also available for across lite a s a .puz here)

by Chris Reeves

The Search for Meaning (at least 70 words and phrases)

An Almost Everything Sud🥯ku

DURING QUARANTINE, SOMETIMES LESS IS (R STEVIE) MOORE

Jesse Malmed is an artist, curator and educator living and working in moving images, performance, texts, occasional objects, platforms and Chicago. His platformist and curatorial (co-)involvements, engagements and entanglements include the Live to Tape Artist Television Festival, the Nightingale Cinema, Western Pole, Trunk Show, the Artists’ Karaoke Archive, ACRE TV and a series of clues left scattered around Ste. 114A. Originally from Santa Fe, he earned his BA from Bard College and his MFA from the University of Illinois at Chicago. He teaches at UIC and UWM, serves as a semi-permanent guest host for Bad at Sports and makes hand-crafted artisanal memetics at @jersimemeblatt.

Jesse Malmed worked on this piece with Stella Brown, the Quarantine Times Sunday editor. Each week, Stella selects a Chicagoan to share a commissioned creative response to the pandemic.