Quaranzine: A printed space for creative work produced during the COVID-19 pandemic

03/27/20

by Marc Fischer

By Friday, March 13th, I felt the full importance of staying home to slow the spread of coronavirus, and so I began to shelter in place. With the exception of a quick trip to Walgreens to pick up a prescription, one more grocery trip, and walks outside away from people to get air and move my legs, I’ve been hunkered down at home with my wife, an academic advisor who is now working remotely. We have enough space that we aren’t on top of each other all the time. We are extremely lucky.

Most of the things I want to do creatively and am employed to do are not possible now. I have an artist residency I administrate as Public Collectors, the name of one of my projects, where I bring other artists to observe Criminal Court with me. We share a meal and a conversation about what we saw, and later those conversations are published as booklets. In the last two years we have observed the trial and sentencing of ex-CPD murderer Jason Van Dyke, hearings for police torture survivor Gerald Reed, and countless court dates for people with minor drug offenses whose only reason for being in jail between court dates was their inability to post bond in a system that’s weighted against the poor.

I had planned to visit court with an artist on that Friday, but the resident cancelled due to some bad luck with their schedule. I had thought about finding an alternate to join me, but there was no chance I would try to visit the filthy court building on 26th and California during a pandemic that was spreading fast. A public defender friend once posted photos of a raw egg that someone dropped or cracked near a railing in one of the stairwells. Then he posted more photos. Then, later, there were additional photos as the egg began to change color and texture. I finally found the egg on my own and showed it to people when we observed court. Fifteen months later, it was finally noticed by cleaning staff and removed. That dried egg and coronavirus would have been besties for sure. Now we are learning that prisoners and staff at Cook County Jail across the street have the virus.

Another Public Collectors project I work on is a publication series called Library Excavations, where I explore the holdings of Chicago’s public libraries and make booklets in response to what I find. Libraries are impossible environments to properly disinfect. You can hardly sanitize the most essential details, like the buttons on an elevator or the handle on a water fountain, much less the keys on every keyboard or the covers of slick, laminated books. Instead, I began exploring the neighborhood boxes on sticks, known as Little Free Libraries, and started posting photos on Instagram (@libraryexcavations). Unfortunately those boxes are mostly filled with generic children’s books, uninteresting religious stuff, and Sarah Palin’s autobiography (which is probably also uninteresting religious stuff).

My opportunities to work were rapidly shutting down. My teaching jobs, which are in a college, in a high school in Chicago, and in an elementary school in Park Forest, have been put on pause until the classes and programs eventually move online, resume, or cease to exist for the year. A book fair in Los Angeles that I was set to attend for Half Letter Press, the publishing imprint I co-run, has been canceled. A zine fest and event I could have been planning for in Madison have also been postponed, indefinitely. Two guest lectures aren’t happening. Mail orders for books through the Half Letter Press webstore came grinding to a near halt two weeks ago, and anyway I’m not setting foot inside a post office unless it’s absolutely essential.

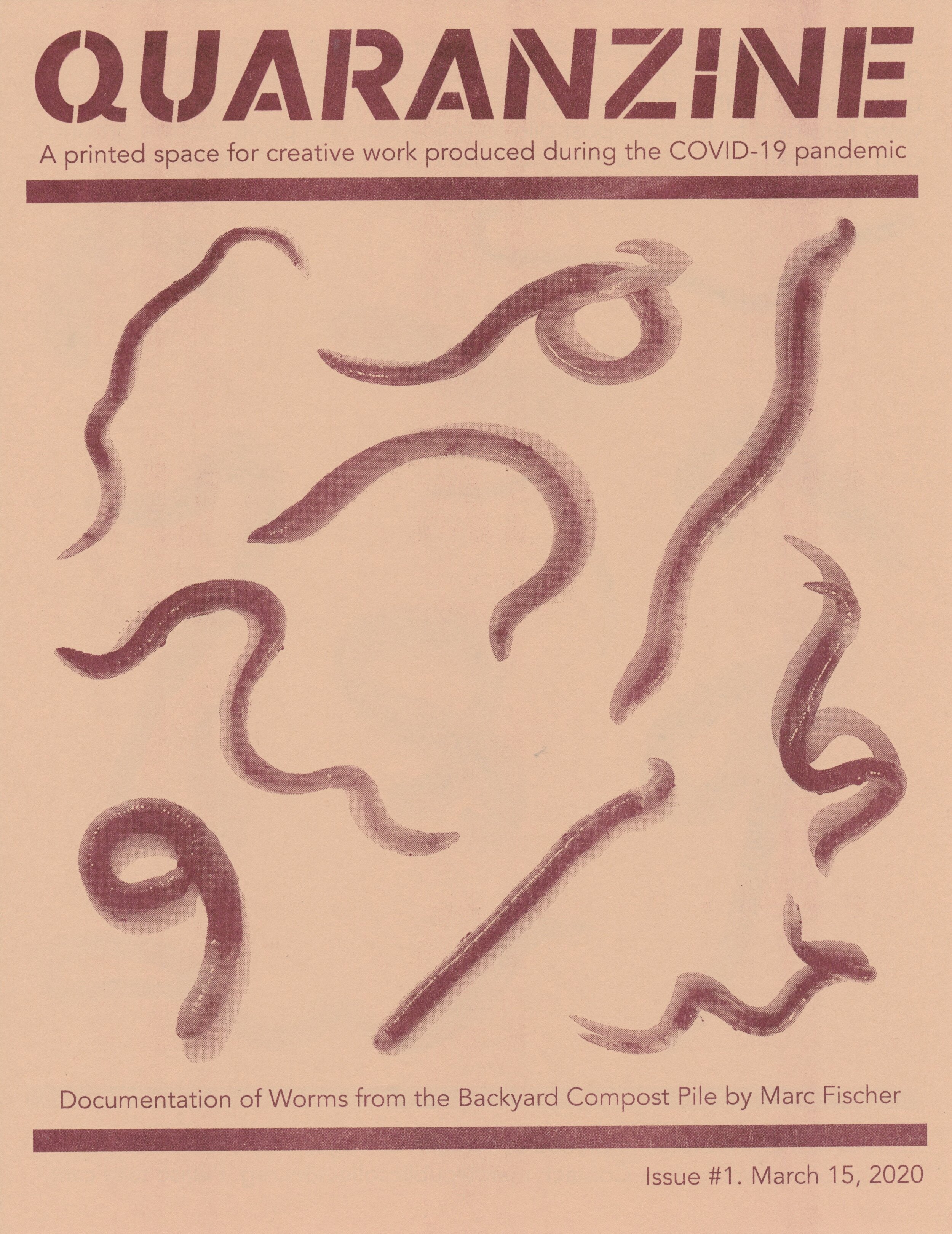

I have made books and booklets and zines for over thirty years, and I felt that making another publication should be my immediate response to the crisis. I had started an essay about paper waste in publishing with Brett Bloom, my collaborator in the group Temporary Services. But that was just one project, and I like to have many things in the oven at the same time. The name Quaranzine came to mind, which is an idea that many other publishing minds surely had simultaneously. I’m against competition. We can all call our thing a Quaranzine. Sometimes the best title is the best title. I just knew I wanted to make something and hopefully collaborate with others too. Everyone was about to go real stir crazy real fast, but not everyone has the means to print something at home. So on March 15th, using my Public Collectors project name, I published the first issue of Quaranzine.

Quaranzine has all of the ingredients found in a complete publication. There is a title, issue number, date, crediting, and a thematic focus fulfilled through both sides of a single sheet of paper. Nothing I do or publish by others is simply stream of consciousness. There is always at least some kind of critical editorial process. But I wanted to make things in a way that was fast. I did not want to reinvent the design wheel every day, so I settled on some fonts, came up with a masthead, and created a basic template for each issue. I put the call out to others, deferred to their choices in typography when they had their own favorites, and am just trying to keep it all moving.

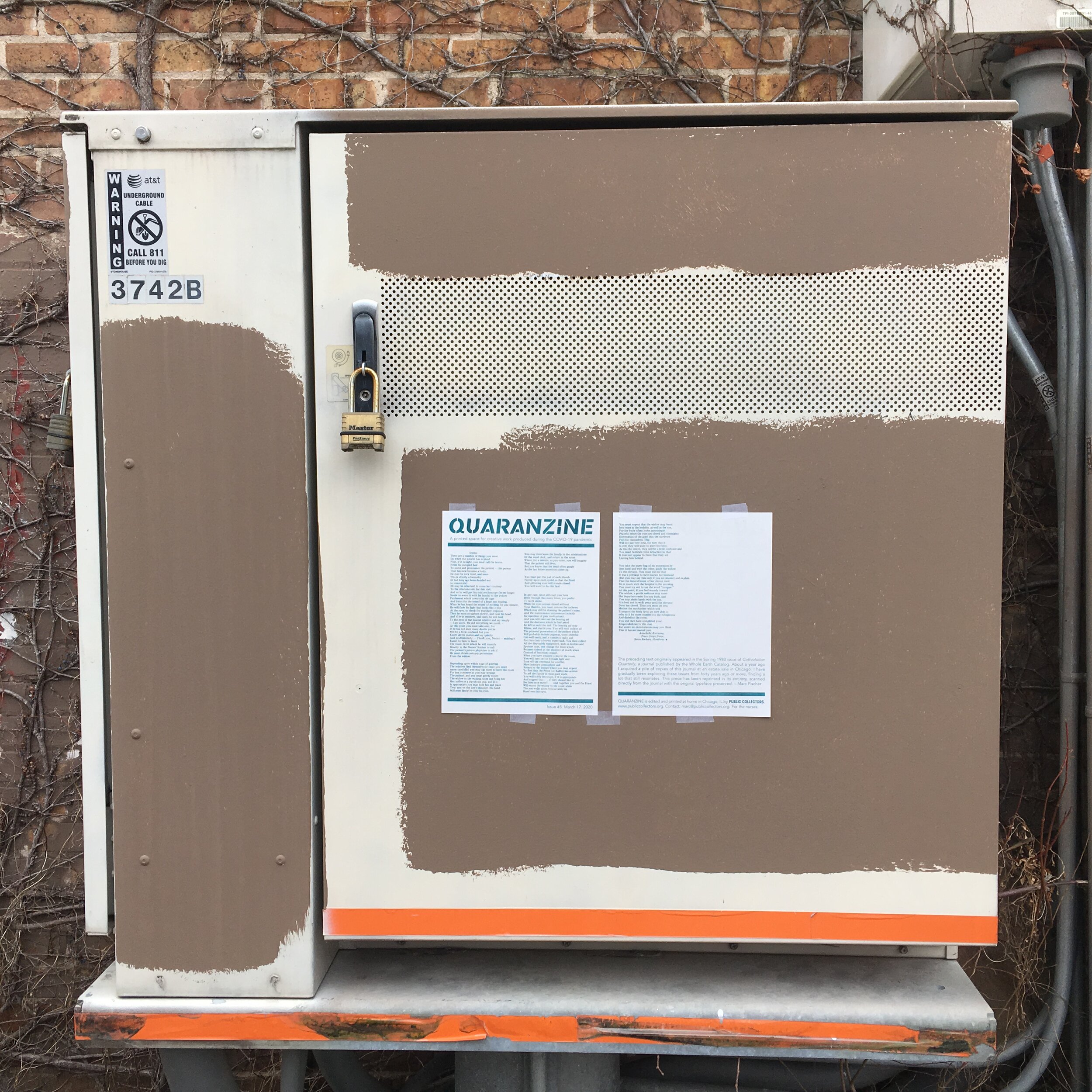

Temporary Services has two RISOGRAPH duplicators. One of them lives in my basement, and I print a lot of publications with it. Usually I like a staple-bound booklet best, but the labor of collating, stapling, and folding is my least favorite part of publishing. I wanted to avoid that, but I also felt like a single, unfolded double-sided sheet might be enough anyway. I love the idea of one-page zines.

Sometimes I go to sleep with a rough idea and then make the entire issue in the morning right after waking up, as though I’m preparing the morning paper. I am reminded of my old friend Bruno Richard, a drawing and publishing maniac from France, who has this ethos that he should make a drawing every day. If he misses a day, he should make two drawings the next day to catch up. That’s the schedule I’m on. Some days I make no publication, so the next day I make two. Sometimes I spend all day picking at the design. Other days someone else provides the content and I quickly throw it together, print it in a couple hours, and go take a nap.

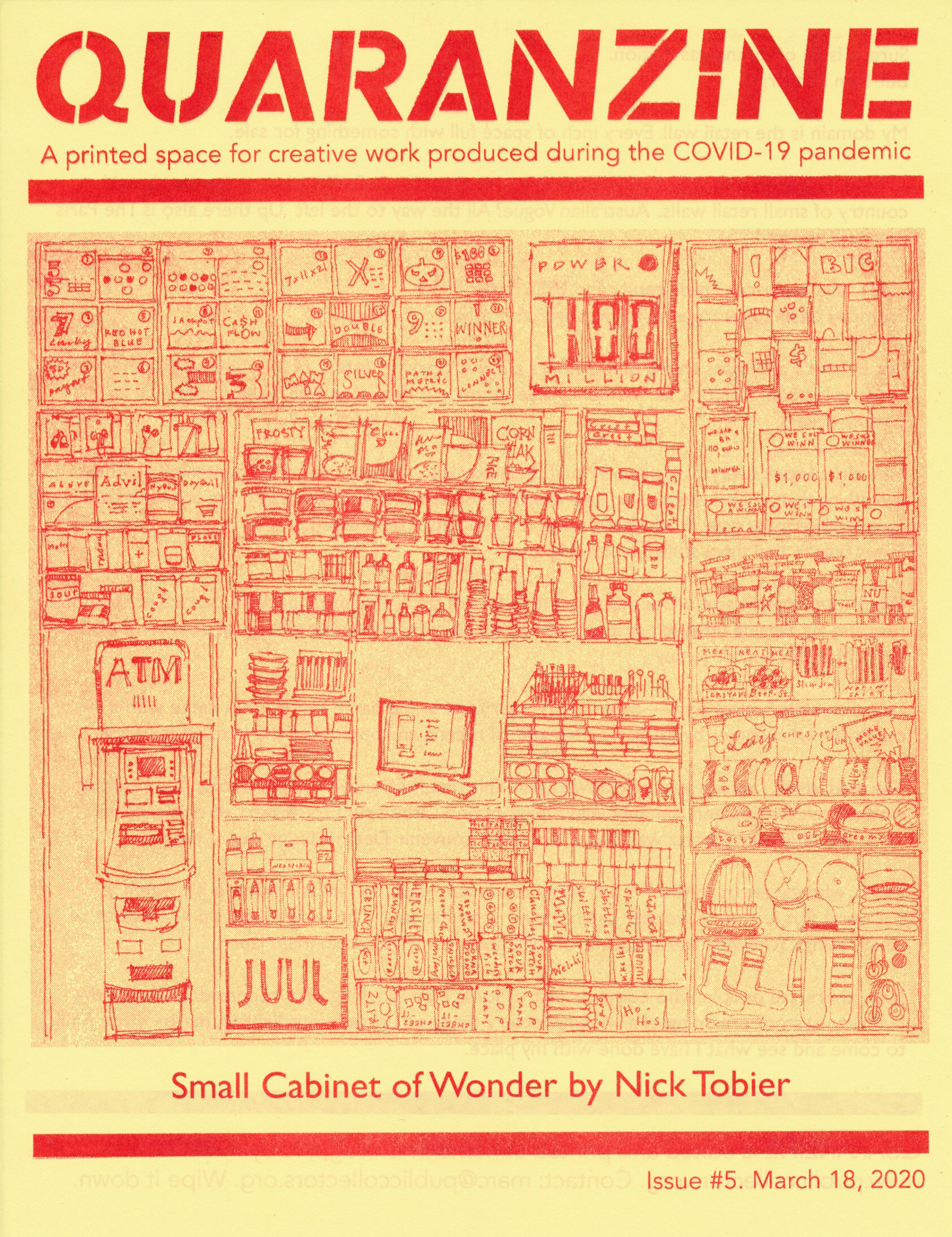

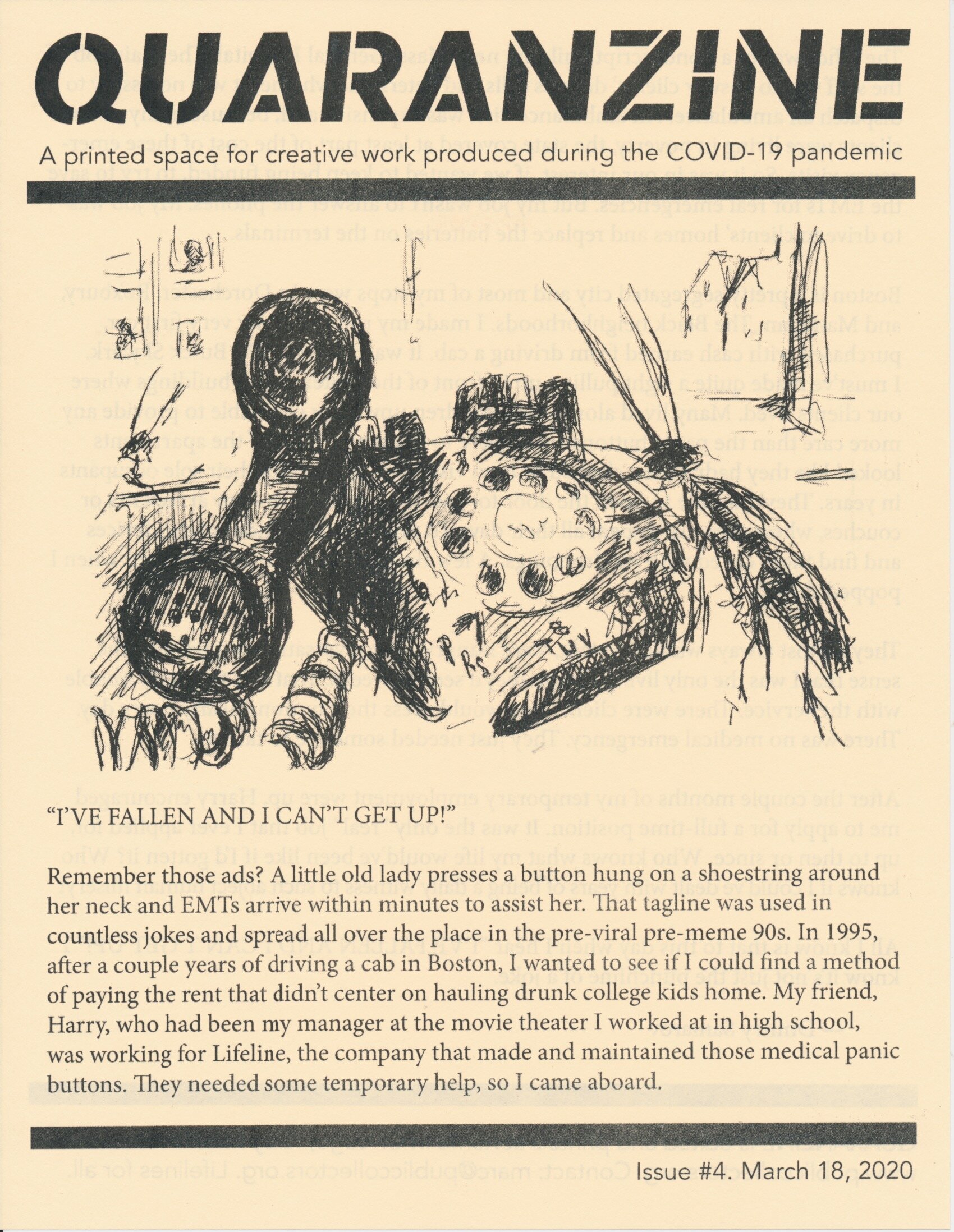

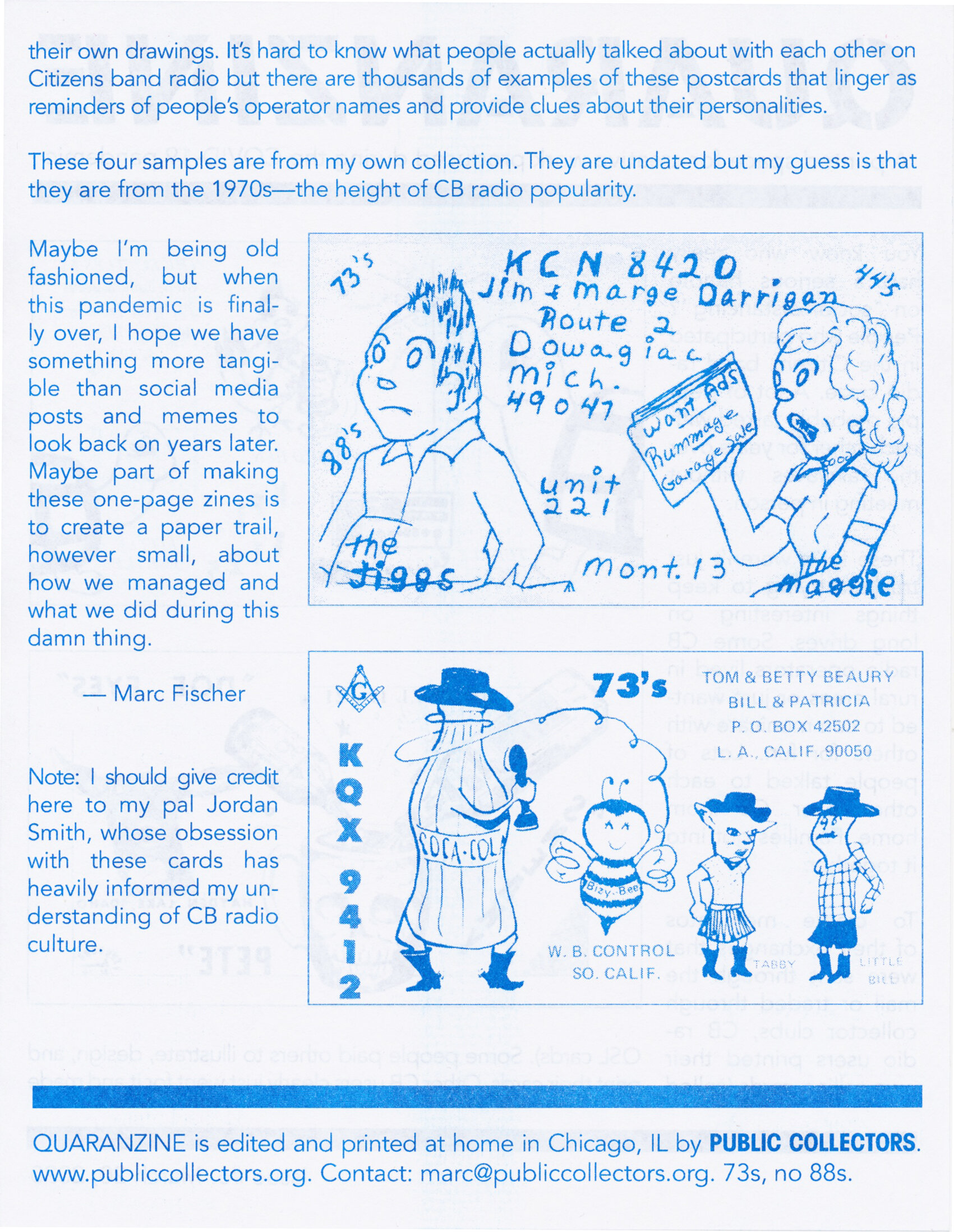

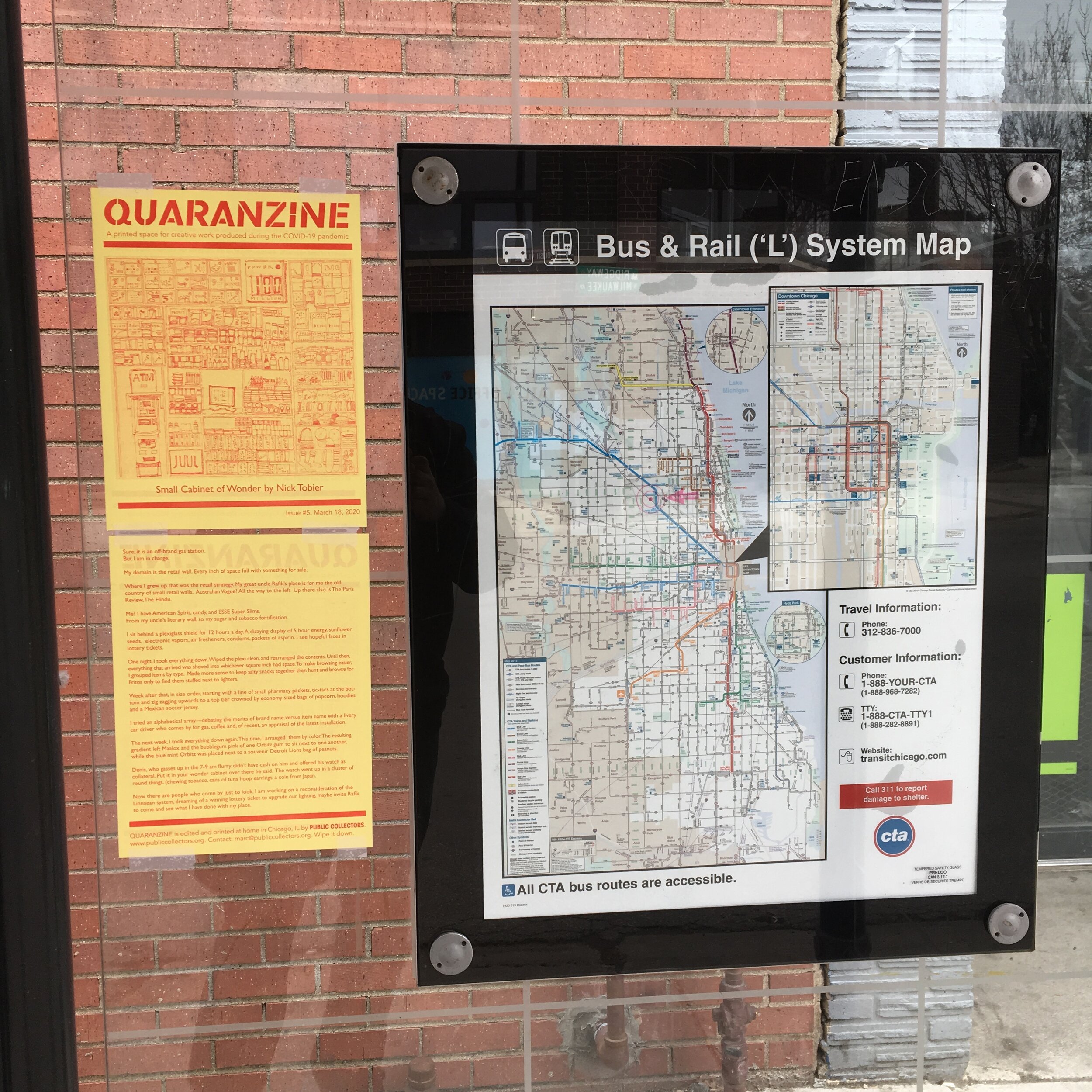

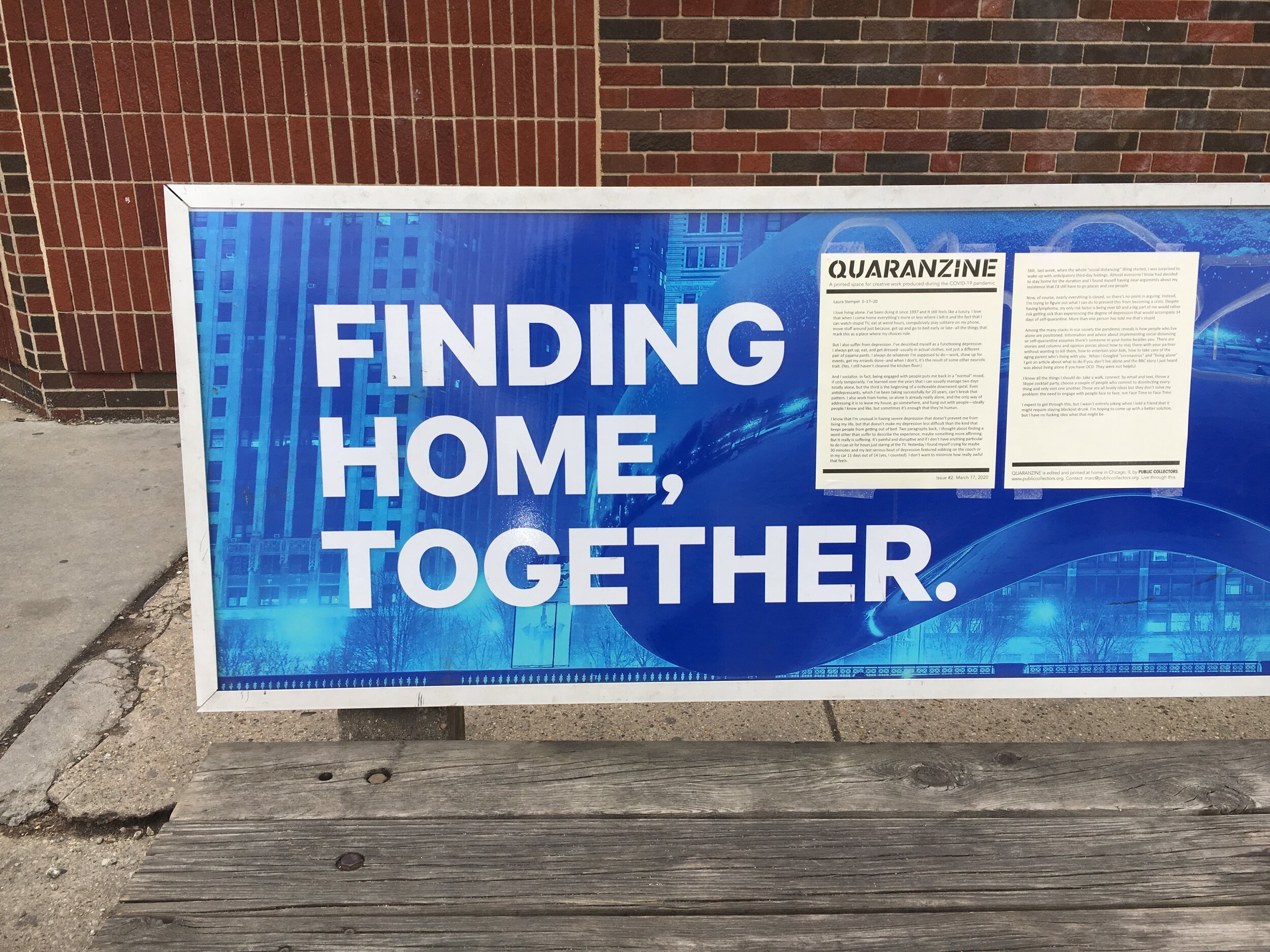

So far the range of Quaranzine themes is broad, and it expands every day. For the first issue, I made photos of the worms in my compost pile in the backyard, and described their blissful ignorance of the virus. It did nothing to stop them from eating their banana peels and coffee grounds. The second issue was written by Laura Stempel, who courageously described the vulnerability she feels living alone with depression during the pandemic. Issue Three reprints a forty-year-old poem from the journal CoEvolution Quarterly, written by a Peace Corps nurse describing the duties involved with handling the dead and relaying news to the family. For Issue Four, Dmitry Samarov drew and wrote about his days working for Lifeline—a company that made a medical alert panic button—and his experiences going to the homes of elderly people who pressed the button entirely because they were lonely and wanted someone to visit. In Issue Five, Michigan artist Nick Tobier drew his version of a display case behind glass in a gas station shop, and wrote a story about how the owner continually develops creative new ways of organizing all the merchandise as if it’s an art project. I wrote about the postcards that people who communicated on CB Radio made in the 1970s, and how Citizens Band Radio aficionados were masters of social distancing. My dear friend Doro Böhme died on March 20th, and that next day I wrote a tribute issue about her photographs, while also including the painful note that there cannot be a memorial or service at this time because of the virus.

A lot of other publishers and zine makers are doing similar activities, but some are only available as PDFs for download. I like online viewing—and it works well for a thing that’s just two sides of a page—but for me, the zine has to be printed. To me, that’s what makes it real and solid and confirms every design decision. I’m working with ink and paper I already have on hand, and the printing reveals the limitations of my selections.

At least some copies have to be shared in open air too—not by getting together with people, but by taping the zines to bus benches, street poles, and dumpsters. People still want to get their steps in and walk their dogs. The length of each issue is perfect for a quick read while there is still a chill in the air. Scanned versions of every finished issue can be read here: https://publiccollectors.tumblr.com/tagged/QUARANZINE

I have no idea how many issues of Quaranzine I will publish, but I expect it could continue for the length of the pandemic. I am starting to find collaborators in other cities that I have never met. This morning I finished Issue Ten. Eventually Quaranzine will serve as a concrete physical record of what some people thought, how we managed, and hopefully, how we survived. I will collate a number of copies into complete sets, and make sure that some go to libraries. Our responses to this crisis can’t be only social media posts and memes. I only print about a hundred copies of each issue, but I hope that this is enough to serve as one model for democratic creative action during a full-blown emergency.

Marc Fischer is a contributing editor for Quarantine Times.

Marc Fischer is the administrator of Public Collectors, an initiative formed in 2007. Public Collectors aims to encourage greater access and scholarship for marginal cultural materials, particularly those that museums ignore. Public Collectors’ work includes the Library Excavations publication series and web project, the Tumblr blog and publication series Hardcore Architecture about underground music in America, and Malachi Ritscher—a project about the late Chicago documentarian and activist, produced for the 2014 Whitney Biennial. Most recently Public Collectors has initiated the Courtroom Artist Residency. For this project Fischer brings artists to observe Criminal Court in Chicago followed by a discussion over a meal at Taqueria El Milagro in Chicago’s Little Village neighborhood. The conversations that happen after court, along with additional writings, have been turned into a publication series: The Courtroom Artist Residency Report. In addition to Public Collectors, Fischer is also a member of the group Temporary Services (founded in 1998) and a partner in its publishing imprint Half Letter Press (ongoing since 2008). Temporary Services and Half Letter Press have produced over 125 publications and Fischer has created nearly 45 publications under the Public Collectors imprint. He is based in Chicago.