Are You A Foreign Artist? - Round Two

05/13/20

By Lori Waxman

“Are You A Foreign Artist?” is series of reviews written by art critic Lori Waxman, in partnership with Li-Ming Hu during her solo exhibition DISCOmbobulation at Co-Prosperity Sphere.

The following reviews were written between 3 and 9pm on Saturday, February 15th, 2020.

Round 1, written on February 1st, and Round 3, written on February 22nd, have also been published on Quarantine Times.

Cherrie Yu, “Cherrie and Matthew,” 2019. Image courtesy of the artist.

Cherrie Yu

"Cherrie and Matthew" is a dance, and a film of a dance, in which the two titular people do many of the same motions. They swing their arms, wave their hands, reach high, sweep with brooms, kick, bend, etc. Some of these gestures are familiar from contemporary dance, including pieces by Trisha Brown and Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker. Others come from the work that Matthew does in his day job as a condominium maintenance worker. This makes sense: Brown, de Keersmaeker and others of their generation were interested in vernacular movement, and vernacular movement is what Matthew must do every day, no matter how repetitive it gets. The radicality of Yu’s performance is her direct collaboration with the everyday person, rather than her theatrical citation of their labor. Both worker and dancer speak, contribute, act, and analyze. It wouldn’t have happened without Cherrie and it would be nothing without Matthew. “Why the hell not,” Matthew responded to Cherrie’s initial invitation. Indeed.

—Lori Waxman 2020-02-15 3:34 PM

Hyun Jung Jun, “Teyo’s Lightshield” (detail), 2019. Image courtesy of the artist.

Hyun Jung Jun

It can take me hours to prepare a meal that my family consumes in fifteen minutes. That’s okay, not everything in life must total an equivalent end product. Many such unequal-seeming equations explain the output of Hyun Jung Jun: elaborately lumpy candles, an endless list of active verbs, eggshells that sprout nasturtiums. She has cut and markered hundreds of shiny little strawberries in a rainbow of colors, written words in a carpet of dirt, tenderly enlarged old grocery lists. Cats lurk in her paintings, of course, because cats are both otherworldly and totally quotidian, marvelously languid and terrifyingly fast. How it all fits together is how it all fits together: not everything can or must make perfect sense. Two hours of cooking does not equal two hours of eating. Except when it does.

—Lori Waxman 2020-02-15 4:09 PM

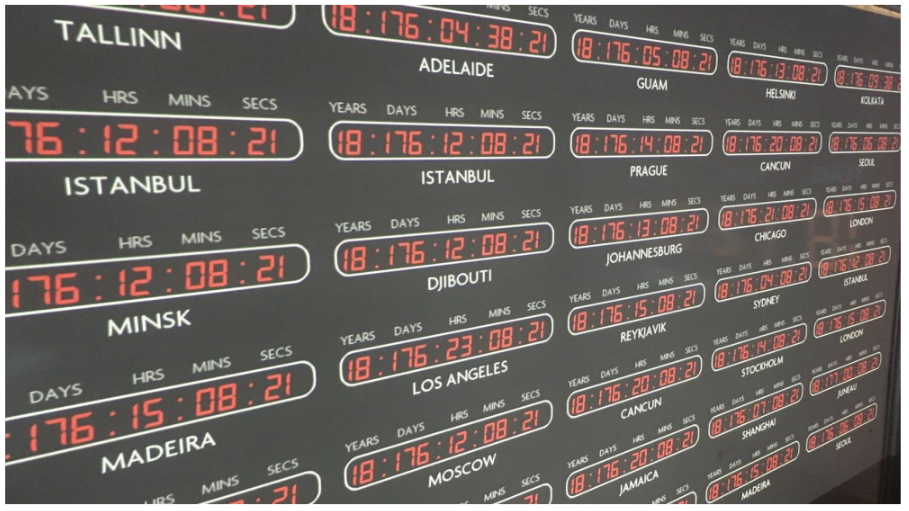

Amay Kataria, “Two Degree Window,” 2019. Image courtesy of the artist.

Amay Kataria

The world has been digitized. This is true of people’s attention, attracted this way and that by phone and desktop apps; money, funneled evermore through cryptocurrency; statistical analysis, which can compute information greater and faster; and even human communication, arbitrated by social media and voice-activated software. But has the world been improved? Amay Kataria’s artworks use sophisticated computer coding, interactive software, and more to interrogate the seemingly intractable place of technology in the world today. His grandest proposal takes data visualization to a whole new level: a doomsday clock counting down the time until a disastrous two-degree rise in global temperature is no longer avoidable. Kataria envisions this hi-tech timer front and center in Times Square, in Tokyo’s Shibuya district, and on the Eiffel Tower, proposing that what got us into this mess in the first place, if used judiciously, might get us out, just in the nick of time.

—Lori Waxman 2020-02-15 4:49 PM

Angeliki Chaido Tsoli, “Attempting to reach equilibrium in times of dystopia” (still), 2017. Pmage courtesy of the artist.

Angeliki Chaido Tsoli

A woman crosses the road with a tire. A woman interviews people about their financial debts. A woman tries to stop the passage of time. These could be the first lines in a riddle, and in some sense they are, of the riddles that are the deceptively simple gestures and tools of Angeliki Chaido Tsoli. Tsoli repeatedly seeks what has become so tragically hard to achieve in our dystopian times: some kind of balance. In her attempts, she is sincere, generous, friendly, and also a little bit absurd. At dfbrL8r gallery recently, as the opening event of the venerable performance space’s 10 year anniversary celebrations, Tsoli flew from her native Greece to Chicago, trekked across the cold city with a suitcase, greeted everyone in the gallery personally, gave them each a commemorative sticker, unpacked and built and hung a flag, and hung also a Polaroid that documented the final moments of a past performance project. How do we keep a moment alive, she asked? And she answered: by documenting it, sure, but also by sharing it with others.

—Lori Waxman 2/15/20 5:21 PM

Noa Ginzburg, “Extra Ocular Object Number Seven,” 2020. Image courtesy of the artist.

Noa Ginzburg

Imagine the therapeutic participatory sculptures of Brazilian modernist Lygia Clark, her so-called relational objects, and cross them with the junk combinations of Robert Rauschenberg, then pass them through the sieve of forced migration and its obligation that one be ready to pack up and go at a moment’s notice. Do that and you might, if you’re very lucky, end up with Noa Ginzburg’s marvelous “Extra Ocular Objects.” Three of these impermanent constructions will be on display at the Langer over Dickie gallery, and the intrepid visitor will not simply look at but with and through them. “EOO Number Five,” a hanging clump of ribbons, twine, crocheted yarn and sequin threads, is my favorite of the lot, especially when a person sticks their head into the mix, extending the sculpture to the length of their body, funneling their eyesight through two suspended viewfinders, allowing the EOO to transform into a puppet, a mask, a kinetic construction, and themselves into a performer. What do they see? You’ll have to try it to find out

—Lori Waxman 2020-02-15 5:49 PM

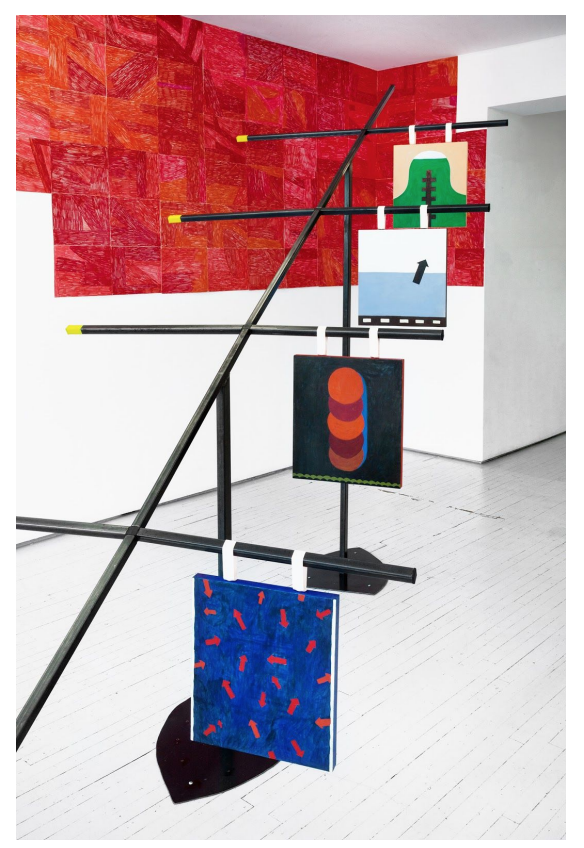

Anna Sophia Vukovich, “Where is your/ The Compass,” 2018. Image courtesy of the artist.

Anna-Sophia Vukovich

Sometimes everything’s up and then everything’s down. Some days I swear I even feel sideways. At Erin Stump Projects in Toronto, Anna-Sophia Vukovich’s “Where is your/The Compass” provides visual aids for keeping track of emotional coordinates, your own and the world’s. In the center of the gallery, a steel structure modeled on a weather vane offers four bars on which to hang your choice of seven hand-painted signs, whose friendly geometric language will hopefully provide a visual symbol of the moods you are sensing. Life feeling too chaotic? Try the handful of red arrows scattered in every direction on an azure background. Loneliness lurking everywhere? That black circle suspended on a grey ground seems just right. Things looking up? The single black arrow rising on a slight tilt, that’s the one. Real weather vanes measure what’s happening in the air at any given moment, and I suppose Vukovich’s could too, depending on the sensitivity of its participants. But it could also be aspirational, marked by our hopes for how the wind might change. Way finding meets way seeking.

—Lori Waxman 2020-02-15 6:23 PM

Sam Thomas, “Pakeha Gifts,” 2019. Image courtesy of the artist.

Sam Thomas

Sam Thomas is a Pakeha, a white New Zealander, and in this solo exhibition at Bowerbank Ninow in Auckland he made a number of sensitive sculptural gestures in acknowledgment of that complex reality. Intensified by its exhibition in 2019, the 250th anniversary of Captain James Cook’s landing in the port of Gisborne, “Pakeha Gifts” features a handblown glass chandelier in the shape of a bunch of yellow and green plantains, and a wall hung with forty cast-recycled-aluminum patu (a short Maori club). The installation remakes important local trading objects into elegant replicas, but in that translation much that is not always so tidy comes to bear: the fate of forty brass patu made for but never re-gifted to the Maori by Cook’s boatmate Joseph Banks, the massive Tiwai Point aluminum smelter owned by the multinational Rio Tinto, the relationships Thomas himself has with artisans, and the availability of raw materials in the places where he lives. This has always been the basis of world trade: materials, relationships, obligations, currency, transformation. The radicality of Thomas’s version is the thoughtfulness with which he acknowledges his own place in that economy.

—Lori Waxman 2/15/20 7:17 PM

My Linh Mac, “Olive Forest,” 2019. Image courtesy of the artist.

My Linh Mac

I have long been jealous of the Victorians, whose every book was bound by marbled endpapers. The bubbly swirls, the murky depths, the irrational curves—what better way to approach and depart from the other worlds contained within the pages of a great book? In her “Ranbu” series, Millie Mac has created a painter’s version of this lost literary treasure, bound by a white canvas frame rather than cloth-bound boards. Using acrylic paints mixed to varying degrees of viscosity and eschewing a brush for the tools of palette knife and gravity, Mac creates strange and wondrous panels as gaseous as they are liquid, as luminous as they are cavernous. No wonder that she has borrowed the Japanese word for “wild” as her series title. But the chaos is ultimately controlled, encased in layers of thick glazing, which present a surface as smooth as a ceramic plate—and you’re allowed to touch!

—Lori Waxman 2020-02-15 7:55 PM

Jack Hogan, “Cows and Flies” (still), 2020. Image courtesy of the artist.

Jack Hogan

I have always loved looking at maps. And cows. So Jack Hogan’s video, “Cows and Flies,” pleases me immensely, for how it explores the flattening and distortion of the spherical world created by reducing it to two dimensions; for retelling beloved stories about the absurdities of adults and language; for spending real time with a herd of cattle and making a one-to-one photographic print of them and then putting a herd of humans underneath it; for trying to draw longitude and latitude lines by stringing colorful ropes across a field in a grid; for acknowledging that the drone technology that allows them to film a farmer’s field from above is the same technology that allow for all kinds of new surveillance and extraction; and for a whole lot more, still, for far too many sensitive and unexpected observations to do justice to here, even in a massively run-on sentence. But not for the flies, no not for the flies. The cows never seem to mind them, though I always do. One wonders what the herd thought of the drone overhead, with its incessant buzzing.

—Lori Waxman 2020-02-15 8:29 PM

Dier Zhang, “Comfort Touch,“ 2019. Image courtesy of the artist.

Dier Zhang

Most of us do not give a whole lot of thought to the functional objects that we encounter in the kitchen, at the library, at the doctor’s office. Dier Zhang does, with a wry sense of humor that refuses to take any thing for granted. In “Comfort Touch,” a deceptively simple zine, she pairs gynecological instruments with the kitchen tools they resemble—think forceps and tongs, speculums and can openers—setting off a domino effect of feminist deconstruction. Why are the metal objects made and marketed for women so violent? One wonders if female designers might have imparted a more comfortable touch. In “Make/Use,” Zhang tests that theory out, allowing liquid resin in plastic bags to harden in specific places, taking on the shape of a corner that needs a wall hook or a row of books that needs a stopper. The results are uniquely harmonious and individualized meldings of object, need and site, as those gynecologists, with their bayonet shaped vaginal retractors, certainly never managed.

—Lori Waxman 2020-02-15 9:08 PM

Lori Waxman (b. Montreal, Canada) has been the Chicago Tribune’s primary freelance art critic for the past decade. She teaches at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and has a Ph.D. in art history from the Institute of Fine Arts in New York. Her "60 wrd/min art critic" performance has been exhibited in dOCUMENTA (13) and a dozen cities across the U.S. She has received a Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant and a 2018 Rabkin Foundation award, and is the author, most recently, of Keep Walking Intently(Sternberg Press), a history of walking as an art form.